by Jason Sams, Lead Developer

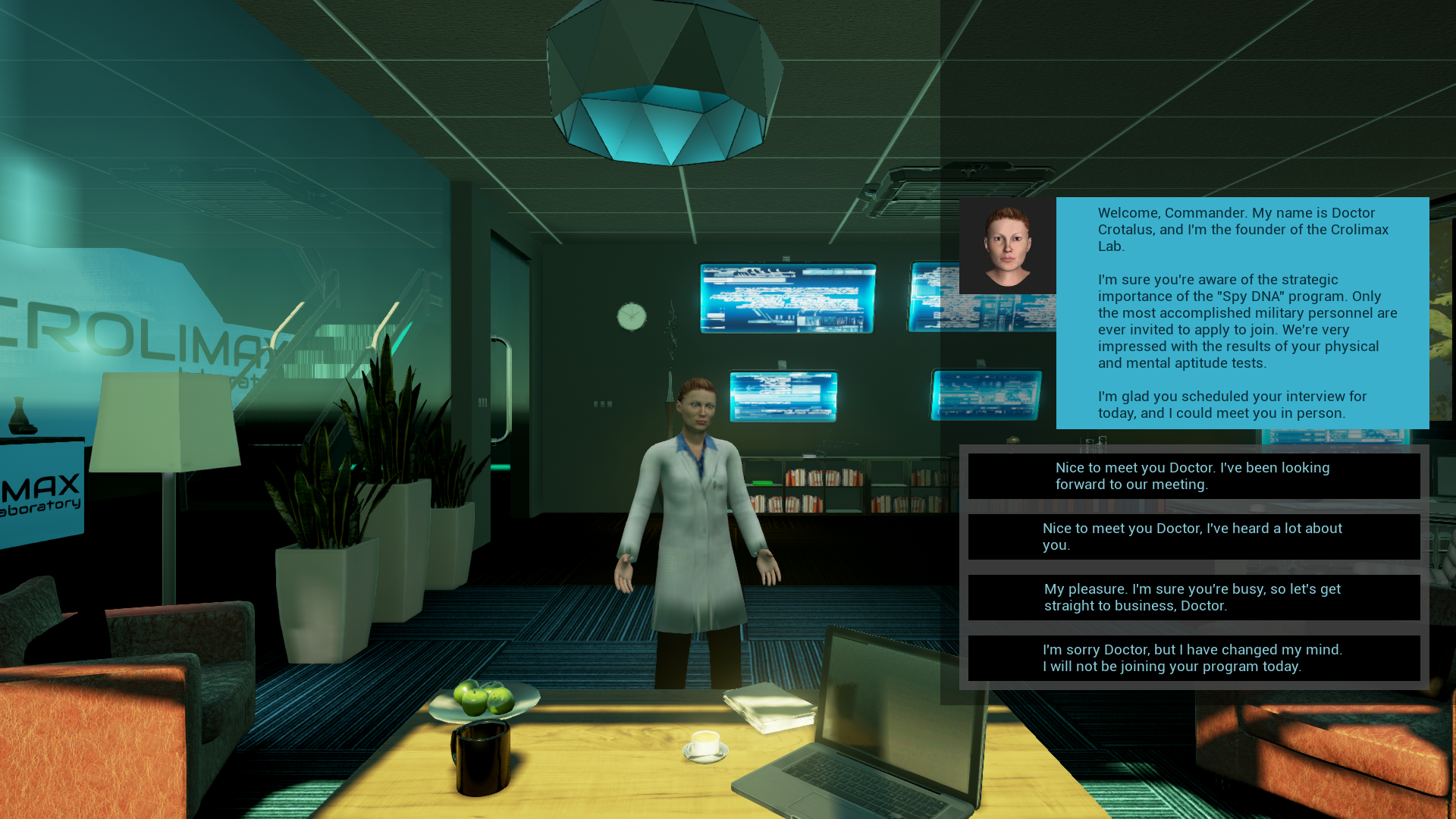

We have been hard at work creating missions. Part of this work has been to test our model of how the player interacts with the world in-game. We have talked about combat interactions in the past, and this month I’d like to cover the non-combat interactions.

We use a five-segment menu for our interactions with the world. The center action is the default action. If you quickly left click an interactable object it will select this action. The mouse cursor changes to reflect this default action. This is to allow the player to know what will happen without having to wait for the menu to appear.

Around the center there are other actions that will appear after a very short delay. The bottom option will always be examine. We always show this option, even for non-interactable objects to avoid leaking which objects are interactable and which are not.

On the right we will display an aggressive action, if applicable. For example, break down a door, attack an NPC, or trip a trap. The option displayed will change with the object. The available options are set as part of the object editor.

For the other options we will place a stealthy action on the left, if applicable. For example, sneak if moving, lock-pick to pick a lock. On the top will be a neutral action, again if applicable. Examples, knock on a door if locked, lock if unlocked.

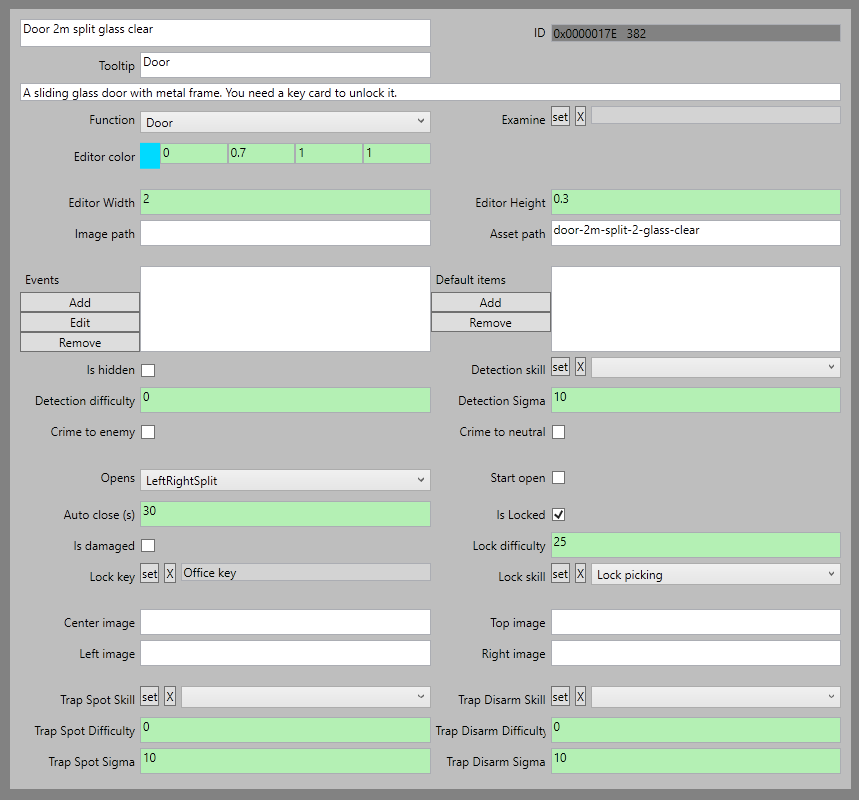

Locks:

Doors and containers may be locked. Once you are close enough to interact the cursor will change to a lock if this is the case. Each item will have a lock type assigned which determines which skill (usually electronics or lock-picking) will be needed to pick the lock. In addition difficulty and sigma (see Alex’s post for info), will be set.

Traps:

Items may also be trapped. By default a trap will not be shown unless a character passes an appropriate detection skill check. Once detected, a trapped object will show as trapped, until then it appears normal. The default action for an object, known to be trapped, is to do nothing. This avoids accidentally triggering a trap the character knew about. A trapped object will have three interaction. Examine, disarm, and trip.

Disarming a trap will require a skill check. Success will disarm the trap. Failure will trigger a second check to determine if the trap is tripped. Once disarmed or tripped, the item is considered normal and will return to appearing to have normal function.

Travel objects:

In Spy DNA Spy DNA we have a category of objects used for covert travel. For example ventilation ducts. By default you won’t know where the ducts lead unless you have mapped them during infiltration or via exploring them. Some will require a check against attributes (ex: dexterity, flexibility). A failed check will remove that path as an option for that character. Other character will be able to try, if desired. While attempting the travel the character will be removed from the map and unavailable. Upon a successful transit, the path will be marked and available for that character to use again if desired. Other characters attempting would need to pass the same attribute check.

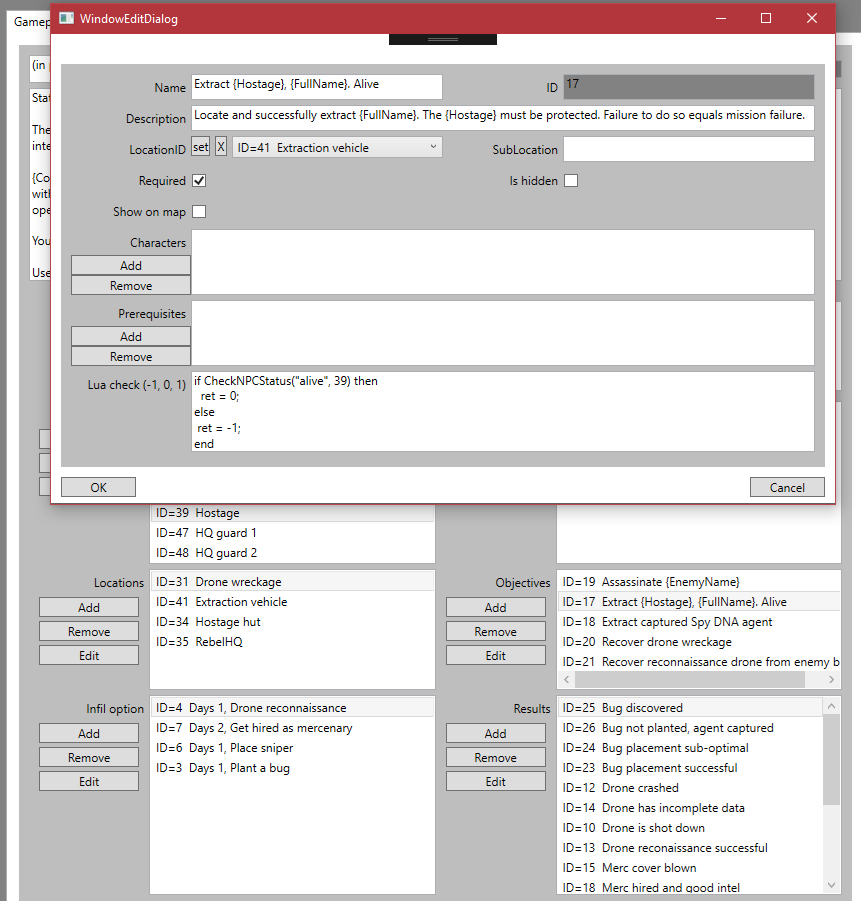

The last category of object is called “custom.” These are unique objects where the options are entered in the item editor. We support overriding all the action slots except “examine” as the bottom option. Custom menu options are used for story-line objects or objectives. Our level designer can use them to trigger unique events as needed.

I hope this gave everyone an idea of what you may be doing when not in combat or talking with NPCs.