By Jason Sams, Lead Developer

I want to talk about complexity in games. I think complexity is a very misunderstood subject. Game developers are sometimes seeking to “simplify” where there’s no need, while at the same time adding complexity without realizing it.

What is “complexity?”

When I say “complexity,” I mean specifically “perceived complexity.” In other words: Is the action considered easy or hard for a human to accomplish?

Here’s a practical example: If I asked you to throw a ball at a target, would you consider that a complex or difficult task? Probably not. However, hitting a target with a projectile is a task complex enough that solving the math behind it drove the creation of the first computers.

When video games were created, lobbing projectiles at things was a rich enough subject that entire games were built around the idea, such as Artillery Duel and Scorched Earth.

Let’s look at a more recent example. Is driving a car complex? Most people consider it so easy that they do all sorts of other things while driving. Yet teams of engineers are still struggling to teach a computer to do the same thing. Analyzing visual data is so challenging, that they have to use additional sensors (Lidar) that humans don’t have, or need. Objectively, driving is very complex and yet it’s still easy for humans.

And again many games are built around the idea of driving (or flying). Most of those games are considered very easy to pick up and start playing. Perfecting your technique and winning is the real challenge.

What about an opposite example? Multiplying large numbers is so simple even a phone can do it a few billion times per second, yet ask a human to do it and many would rather drive to buy a calculator. No one would make a game like this outside of education.

In context of game design, we’re interested in complexity as perceived by a human player. In our case we are specifically interested in making the mechanics of the game easy to grasp. This idea has been a driving factor in the design of Spy DNA and is also the reason for us calling the game a Simulation RPG. (Side note: it’s also led to way more UI iteration than we ever envisioned.)

Our combat system is designed to be the best simulation we can make of combat. We chose simulation and not the traditional turn-based approach to solve the problem of perceived complexity vs. actual complexity.

I’m a big fan of realism in games. Nothing will frustrate me more than when something happens in a game that makes no sense in the real world. Some examples:

1: You move a character one step forward, you trigger an enemy group, that now all get to activate, move several times farther than your one step, and possibly attack and kill your character. All this before you can even react.

2: You find a new item in game, yet you can't use it because of some attribute or skill check. The worst ones are the cases where you lack “strength” to wear an item, yet, toss it in the backpack and you can be lugging several of them around despite them being harder to carry that way.

3: You sneak up behind a target and make a surprise attack. You stealthy weapon fails to penetrate the armor despite hitting a spot where there was none (visually). The enemy then turns around and kills you.

What all these things have in common is they are results of artificial rules imposed by a game system that don’t exist in the real world.

Human brain is very good at understanding natural things such as physics (throwing something), or processing an image, but dealing with large numbers of artificial rules is not something that comes to us naturally. Therefore games that go down this path are perceived as complex for the player.

Not all complexity is necessarily bad. There are many popular games built around artificial rules, chess being the first that comes to mind. Add a little random input and you have pretty much every card game ever. In these cases managing and exploiting the rules becomes the focus of the game.

In Spy DNA, we want you to feel like an agent in a believable world, where things that should work actually do work in-game. Or put another way, we wanted the combat system to be intuitive and realistic. We wanted the game to be about Spy DNA world and not about the combat mechanics.

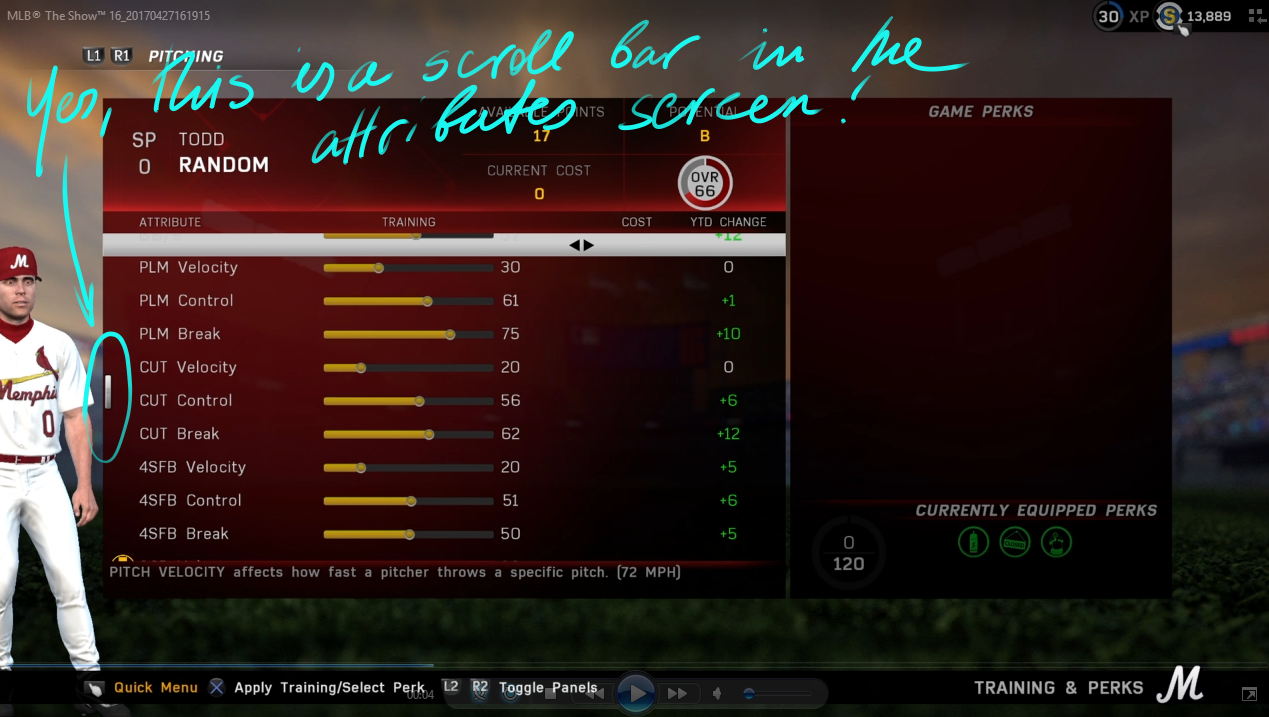

When you play Spy DNA, one of the things you will notice is that we have a lot of attributes compared to most RPGs. I’ve heard people give talks saying that six attributes is too many for an RPG, and I consider that silly. I mean, if a console sports game can have 38 attributes (MLB the show), I don’t see why a serious PC RPG shouldn’t have more than 6.

Yes, this is a scroll bar in the attributes screen!

This is where we clearly see the difference between perceived vs. real complexity. By all accounts the simulation in the MLB game is more complex, but because each attribute is clear and easy to understand and relate to in real-life terms, it never feels difficult to understand or play.

By comparison, when you have too few attributes, the attributes have to stand for things that are not obvious from the name, such as using dexterity for speed, strength for hit points, or intelligence for spellcasting. Each game has a slightly different system, making it necessary for the player to learn a new set of artificial rules with each game. Learning abstract rule sets is a thing that humans aren’t very good at, and therefore perceive it as complex.

How could having more attributes actually make a game seem simpler? The primary way is to map the attributes to “things a human intuitively understands.”

In Spy DNA we have 21 attributes in 7 common groups. We use groups, so that players used to traditional RPG systems would immediately be comfortable. The groups simply provide the average of the sub-attributes for quick reference and ease of picking up the game for those familiar with other systems. Within each group we provide the details, so it’s intuitively clear what’s really going on.

Screen capture of Spy DNA character attribute screen

Let’s looks at dexterity, using the party sniper, Zoe, as an example. At a glance you can see at 81, dexterity is a strength for the character, as you would expect for someone specialized in ranged attacks. However, with our focus on being realistic, we break down dexterity into Dexterity, (could also be called manipulation), reaction, and flexibility. In this example the character has a clear specialization. You can also see from the description she has a “+40 enhancement”. This comes from the genetic enhancements which put the “super” in “Super Spy”. As a result of these you can end up with values in excess of the natural human limit of 100.

Reaction is simply reaction time and impacts reactive movements (duh). In-game it will make you harder to hit in a melee fight, and help with any other action that depends on quick reflexes.

Flexibility is important to martial artists or characters that want to sneak past alarms or hide in places you wouldn’t assume someone normally fits.

By being explicit about the common traits that a character may have, it should be actually easier to parse what the attributes actually mean for gameplay. We feel that this is better than a giant array of perks because it’s clear and straightforward.

When it comes to combat, we try to simulate the world as it is, and not require people to learn a unique set of made up rules just to play Spy DNA. Let’s take cover as an example.

In some games cover is measured in increments (high, low, none), or as a percentage. In these examples the cover makes it proportionally harder to hit the target. So far so good. Now you need a mechanism for attacking a target in cover. So these games introduce the idea of “flanking”, or moving to a position where the cover doesn’t apply. Typically these are done on an all or nothing basis, leading to frustration as your character can clearly see and hit the target, but because you have not triggered the arbitrary rule that says you’ve “flanked” your target, you still miss.

In Spy DNA we deal with this in a straightforward way: if you can see it, you can shoot it. Humans understand intuitively that the more of a target is exposed, the easier it is to hit. How much easier? We solve that problem visually. We present the player with a picture of their character’s viewpoint. You see what is exposed, what the area your shot might land in is, and you make the call based on that. Visual and intuitive.

Screen capture of the gun sight cam, showing circular error probable values

I also want to talk about cover vs concealment in Spy DNA. A real-world consideration is: “Will this thing I am using for cover actually stop the bullets?” If the answer is no, it’s not really cover, but just concealment. You might use a couch or a thin door as cover, but those will only slightly reduce the energy of the shots. So if the enemy gets lucky or guesses where you are on the other side, you’ll still have a problem. The flip side of this is, that if you have a weapon with a high rate of fire and have a general idea where the target is hiding, you may be able to get them through their concealment. Just like in the movies.

This leads to the next bit, damage. In most games once you hit a target, there is a random roll for damage, and possibly a separate random roll for a “critical.” So back to that early example on math, most humans don’t have an intuitive feel for complex equations that don’t mirror something in the real world. So instead of having a good grasp of the actual probability of hitting and damaging a target, players have to develop a feel for a weapon’s effectiveness based on trial and error.

In Spy DNA we invert this equation. Damage is 100% deterministic once you hit a target. How much damage you do is based on three things.

1: What hit the target? Ex:type of bullet, fragment, knife, fist.

2: Where did it hit the target? Ex: head, arm, leg

3: How much energy did it have when it hit? More is better (for the attacker)

Those concepts should be very easy to understand, nothing feels complex about it. However, the actual simulation is very complex. It only takes a few lines of code to implement hitpoints. To simulate injuries, we have thousands of lines of code in Spy DNA.

Spy DNA uses per-polygon collisions to model wounds on a character

Our models have multiple colliders so we can not only figure out if you hit your target (which we resolve per-polygon against the mesh), but also what part of the target you hit. Then our damage code takes over and models a wound based on the results.

This creates interesting situations in-game. Looking over cover is still dangerous, even though you’re 90% covered. Why? Because if the enemy lands a shot, it’s the exposed part that gets hit, which in this case is your head. Sticking an arm out would be much safer.

The last bit I’ll talk about is the passage of time. Most similar games have made the decision to be turn-based. We are a simulation, which means every action you take, takes some amount of time. When in combat, time in Spy DNA only passes while you are doing something. The most similar game I can think of is SuperHot with their tagline “Time moves only when you move.” Time will pass for both you and the enemy when everyone in your party has something to do, even if that something is just wait.

Because you want to be able to react to the changing situation in-game while your character is performing their action, we allow characters to react to perceived threats. A character that spots a new threat will cause the time to immediately stop, so you can change your orders if you desire. This mechanic takes the place of the various “overwatch” systems that most turn-based games have.

The ability to stop time when new threats are discovered allows us to avoid the problem where you need to have characters on overwatch to protect a character that is moving, in case they trigger an enemy reaction. In Spy DNA, if an enemy becomes visible, you can just react to it if you choose. We completely bypass the complexity of having the player figure out which rule they can use to protect them against the AIs use of reaction rules. Instead, you just react to what you see when it happens.

When out of combat, you move the party around in real-time. You can manually enter combat mode if you want, and the game will automatically switch to combat mode when the first shot is fired. Exiting combat mode is always manual, unless the mission is finished.

We have put a lot of thought into how to create as realistic a game as possible, where the world feels natural and real to the player. We want you to enjoy the gameplay and story rather than having to learn and optimize for an arbitrary rule system. For many situations in Spy DNA there isn’t just one “optimal” solution, but multiple ways to accomplish your mission, which frees you up to just play the way you want.